To one who doesn’t have a deep understanding of what a play-based classroom really is, it might appear to be little more than babysitting. But to a teacher who has embraced the concept of learning through play, the classroom is a place rich with content and discovery.

Through the lens of “the purpose of preschool is to prepare for kindergarten”, a teacher might prepare a checklist of concepts she wants her students to learn over the course of the year. She would then write lesson plans that included all of these concepts and come up with clever activities to teach them. I was that teacher once and a typical lesson plan for teaching counting and sorting might include an activity where we sorted the well-known math manipulative bears. As a bonus, we could work on colors at the same time. This type of activity would usually occur during our small group rotations, so that I could carefully monitor how each child was doing to ensure that they were learning exactly what I wanted them to, in exactly the way I wanted it to happen.

This type of lesson plan may have accomplished to some degree what I intended it to–students had ample opportunity to practice their counting skills and I could mark off some data points as I asked what color each bear was. But did my students really walk away from that lesson with any excitement about what they had learned? I can assure you that they did not. Not once did a student ever return to that activity on their own because they found it exciting and compelling.

In a play-based classroom, learning and discovery take place in a much more organic way. As a teacher, I still have my checklist of skills based on my state’s core learning standards that I hope to expose my students to over the year. But I’m not writing lesson plans to specifically teach those skills. Rather, I am strategically choosing materials for the classroom that can support that learning and then guiding children when discovery starts to happen.

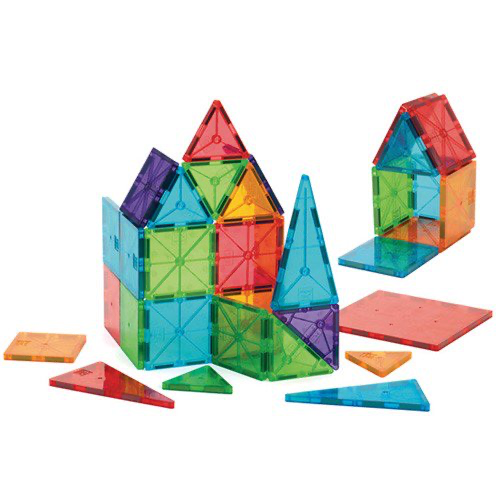

A recent example that my class had a lot of fun with involved Magna-Tiles. This toy is very versatile and a favorite among my students. One day a student stuck two pieces together and then looked through them, amazed to see the blending of the two colors. Knowing that the blending of colors hit on a core preschool skill, as well as the effect light has on different surfaces, I encouraged the process unfolding before me by asking some key leading questions: “I wonder what would happen if you put a third color on your stack?” and “What color do you think you’ll make if you put blue and red together?”.

One student experimenting quickly turned into two students, and then three students, and soon the whole class was engaged. I added some vocabulary to the activity by using the words “filter”, “reflection”, “opacity”, “transparency”, and “blending”. We turned off the lights in the classroom and used finger lights and the flashlight on a phone (two things we had at our disposal in that classroom) to see how they changed the appearance of our magnets. We tried again with the lights on to compare the difference when there was more light in the room. We did not have any windows to the outdoors to use, but that would have added another dimension to our discovery. The kids stacked multiple tiles together and learned that the filter became increasing more difficult to see through. They were all so excited to share their discoveries with one another and it was such fun to step back and watch their learning take place. In this particular school, we rotated classrooms on a set schedule, and our activity had to come to a close much sooner than the children would have liked it to, as we were required to vacate the classroom for the next class to come in.

Later, I was able to reinforce the content learned in other activities: “Remember when we made filters with the Magna-Tiles? What happened when we put blue and red together? I wonder if we would get the same color if we mixed our blue and red paint?”. I was able to observe that the vocabulary used during the activity carried over into other experiences the students had with completely unrelated materials–a few weeks after this activity one student attempted to make a filter with two completely opaque objects and a peer quickly stated that the objects weren’t transparent and couldn’t be seen through, so it wouldn’t work.

I could have easily taught this content while standing in front of the class and showing how to make a filter with two Magna-Tiles. It would have taken less time and been more straightforward. But it would not have carried nearly as much impact as the organic activity that was born out of one student’s curiosity while playing with a toy. My students would have received instruction and information, but they would not have gained deep and meaningful learning.

It does take some extra skill to harness the power of content teaching in a play-based classroom. A solid knowledge of core skills and development must be in place, as well as a keen eye for observation. Flexibility is important, as children may take materials you provide and use them in a completely different way than you expected them to. Teachers need to understand how much to step in and guide and know when it is best to let the learning happen on its own. These are skills that come with practice, and the dividends they pay are priceless!