I have to believe that the intentions of every early childhood program start in the right place. Why else would anybody dedicate so much time and energy to it? It’s certainly not for the money! We do it because we truly desire to see kids grow and learn and succeed. Unfortunately, so many programs fall short of being developmentally appropriate for the children they serve.

A few weeks ago there was an activity on the lesson plan at school that asked the students to draw their own zoo. After the morning session of classes was over, one of my fellow teachers said that her kids were very frustrated with the assignment and had a hard time knowing what to do. Another teacher piped in and agreed, saying her class had the same experience.

I spoke up and said “I can tell you exactly why.” I pointed out that in our program, teachers tell the kids exactly what to do and how to do it and when to do it. All. Day. Long. There is very little choice and our kids have adapted to this model perfectly, as evidenced by the assignment this particular day. When given the freedom to choose, they had no idea what to do.

Programs that lean away from child-lead learning, and instead rely on instruction from the teacher, may not seem problematic on the surface, but they come with some unintended consequences, just like the scenario I described. From the outside looking in, a classroom that is being managed by a grownup may look like a well-oiled machine, but the children inside of it are missing out on learning vital skills.

In the course of this conversion with my co-workers, I let them in on a little secret. My class had completed the activity without any issues because when it comes to “art” in our school, I had gone a little renegade. Before allowing my students to enter the art room, I run in and take down the sample of what we are “supposed” to be doing that day. I don’t want the kids to see it at all–I don’t want them to have any preconceived notions of what is expected of them. I am somewhat bound by the supplies offered to me–always pre-cut pieces, sometimes even partially assembled (and on those days, I often just skip the project all-together and let the kids just draw…if a grown-up is putting most of it together, what is the point?)–but I do the best I can in the situation I’m in.

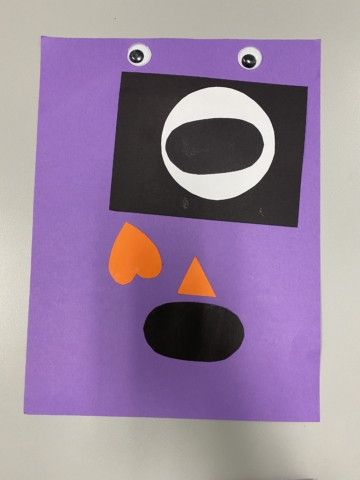

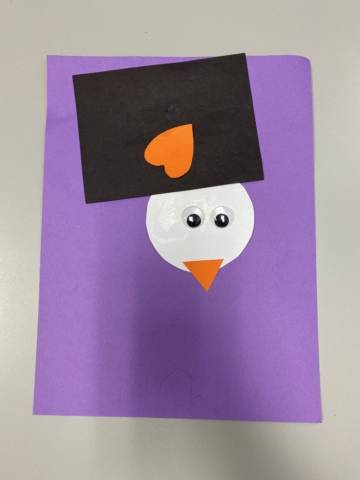

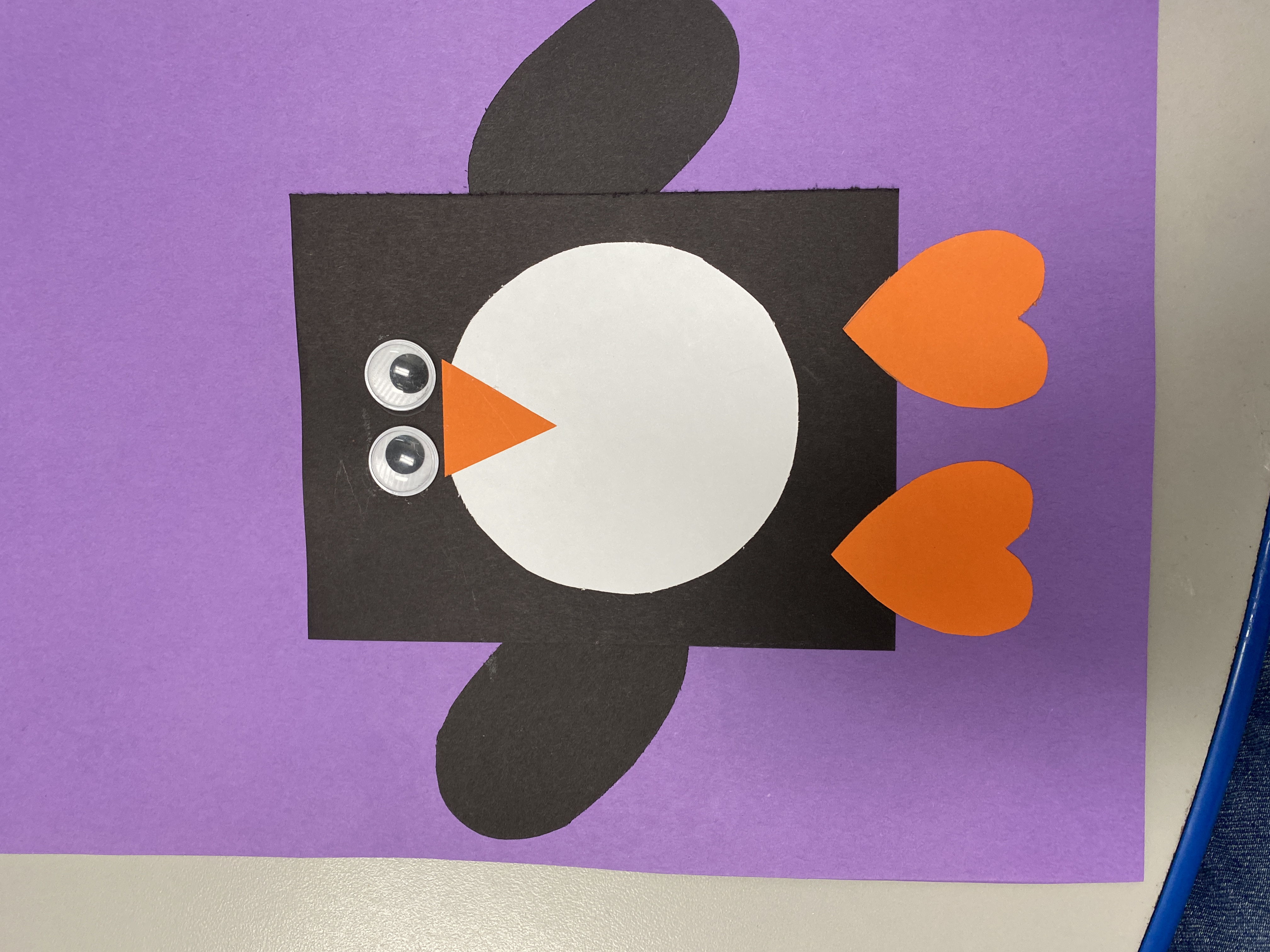

Recently, this was the project-of-the-day:

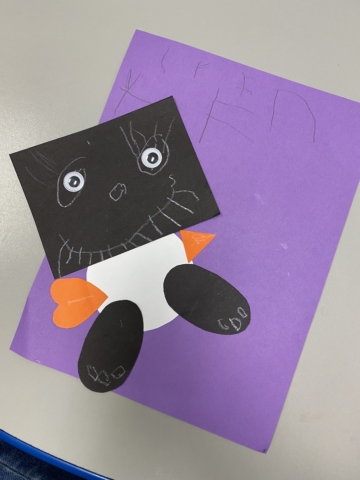

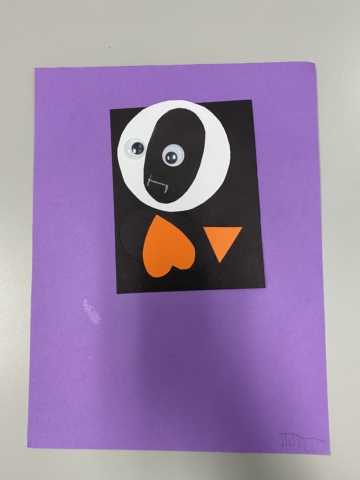

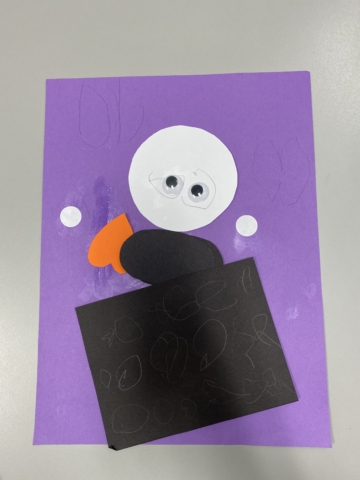

Without seeing the sample, my kids took the pieces they were given and created pictures from their own imaginations. Here is what a few of them came up with:

To a grown-up, they might appear haphazard and nonsensical, but every piece came with an enthusiastic story from the child who made it. They knew exactly what they had created and why. Their piece was unique and different from each of their classmates. And while they may have been perfectly happy to take a penguin home that day, they were truly proud of what they had created from their own imaginations.

After telling my co-workers my strategy, I was surprised at how surprised they were. It was as though they had never contemplated such a thing, but it made perfect sense to them. I respect my fellow teachers and know that they love their jobs–they teach the way they do because they simply don’t know any better (most have degrees in elementary education, and teach preschool the same way they would older children). Armed with a little bit of extra knowledge–and maybe even feeling like I was giving them permission to work outside of the lesson plan–they each pledged that they were going to give this strategy a try. One even offered to remove the sample art for me when her class left the room so that I didn’t have to sneak in and do it myself.

Having taught in a very teacher-led program for the last several years, I have seen first-hand how important it is to give children as many choices as possible in the classroom. Rather than restricting how play materials are used, allow the children to think outside of the box and use them in their own imaginative ways. Instead of offering product art that focuses on how well the child can follow directions to put together a pre-determined project, allow them access to various mediums and time to dig into their own creativity. Offer various activities that cater to a child’s interests and embed academic skills in place of worksheets.

Nobody likes being micromanaged, and that includes children. Students who are told what, how, and when to do things all day long will adapt to that method–but they won’t find joy in it and their ability to learn and grow will be stunted. Choice within the classrooms gives children room to discover in their own unique ways how they learn best, and teachers who have learned to step back and take the role of facilitator and supporter show a great amount of skill.